The Art of the Liminal

The Art of the Liminal by S. K. Kruse was originally presented to the Guild for Engaged liminality September, 2023.

You can listen to the audio above or read the transcript (with pictures!) below.

As I was preparing my reflections on writing and the liminal, it seemed to me that just about everything I had to say could be said for art in general, so the talk I’m presenting today is The Art of the Liminal, starting with:

Part I: Creator as Liminal Being

So my introduction to liminality came through Thomas Moore’s Dark Nights of the Soul about 18 years ago, at a time when I was lost and confused and couldn’t find my way forward. His book not only helped me get through that time but formed in me a deep appreciation—a conviction, really—about the essential part these times of liminality play in our psychic or spiritual regeneration.

And by “liminal” I mean a transitional place or state of being, a boundary or threshold, a time or place that’s betwixt and between.

Unsplash Image via Squarespace

But as much as any of us who have gone through such times might be grateful for the greater freedom we received, we have no romanticized notions about the accompanying suffering of such times. And the next time, eight to ten years down the road, when we sense something in us must change again, we recall the dark night that came before with a sort of holy awe—but terror.

In The Idea of the Holy, Rudolph Otto helps us to understand this type of experience through his concept of mysterium tremendum et fascinans: a mystery before which we are fascinated but tremble, are attracted but repelled. And I think this is a similar—possibly the same—type of experience writers and other artists have when they settle down within themselves to create art.

And I don’t think you can create art without it.

I think if you want to create art you must have a capacity and a willingness to be submerged in an interior liminal state—a contemplative-like state—at the borderlands of the conscious and the unconscious. But to do that you must first overcome your fear of going there.

There’s a great quote Hemingway never actually said: “There’s nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at the typewriter and open a vein.”

Well, whoever actually said it understood the experience well. You know things will flow once you get there, but there’s something prohibitive about it. There’s a fear and a resistance.

I was determined when I wrote the stories in Tales From the Liminal to get into such a state and to stay there while I wrote them, but I felt that resistance every single time I sat down to write. And this was confusing to me because I’ve had a rich interior life from the time I was a little girl. I’ve always enjoyed meditation and dream mining—so why should I be experiencing this sort of resistance?

Some experiences I’ve been having in meditation over the last few years have made me ponder a connection. For the last five years or so, I’ve gotten little glimmers of what I guess I’ll call the dissolution of the self, but I’ve always pulled back from them almost instinctively. One day I hope not to do that, but the point is I think it’s related to the reason I feel resistant to entering an interior liminal state to write.

I know that I’ll be opening myself up to some force beyond my conscious control.

Other voices will take over—sometimes to the point where I feel little more than a scribe furiously trying to keep up. It’s this incredible experience, but it’s really hard to go there because when you enter an interior liminal state, this contemplative-like state with the intention to create, you surrender part of yourself.

This, of course, is a well-documented experience.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Photo from Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Ray Bradbury says, “I don’t write my stories. They write themselves. So out of my imagination, I create these wonderful things, and I look at them and I say, ‘My God, did I write that? Everything comes to me. Everything is my demon muse.’”

In his collection of essays, Zen and the Art of Writing, he describes the Muse as:

And it is an incredible experience, but you can see how a writer—or any artist, for that matter—might feel resistant to entering a state where you feel you’re surrendering control.

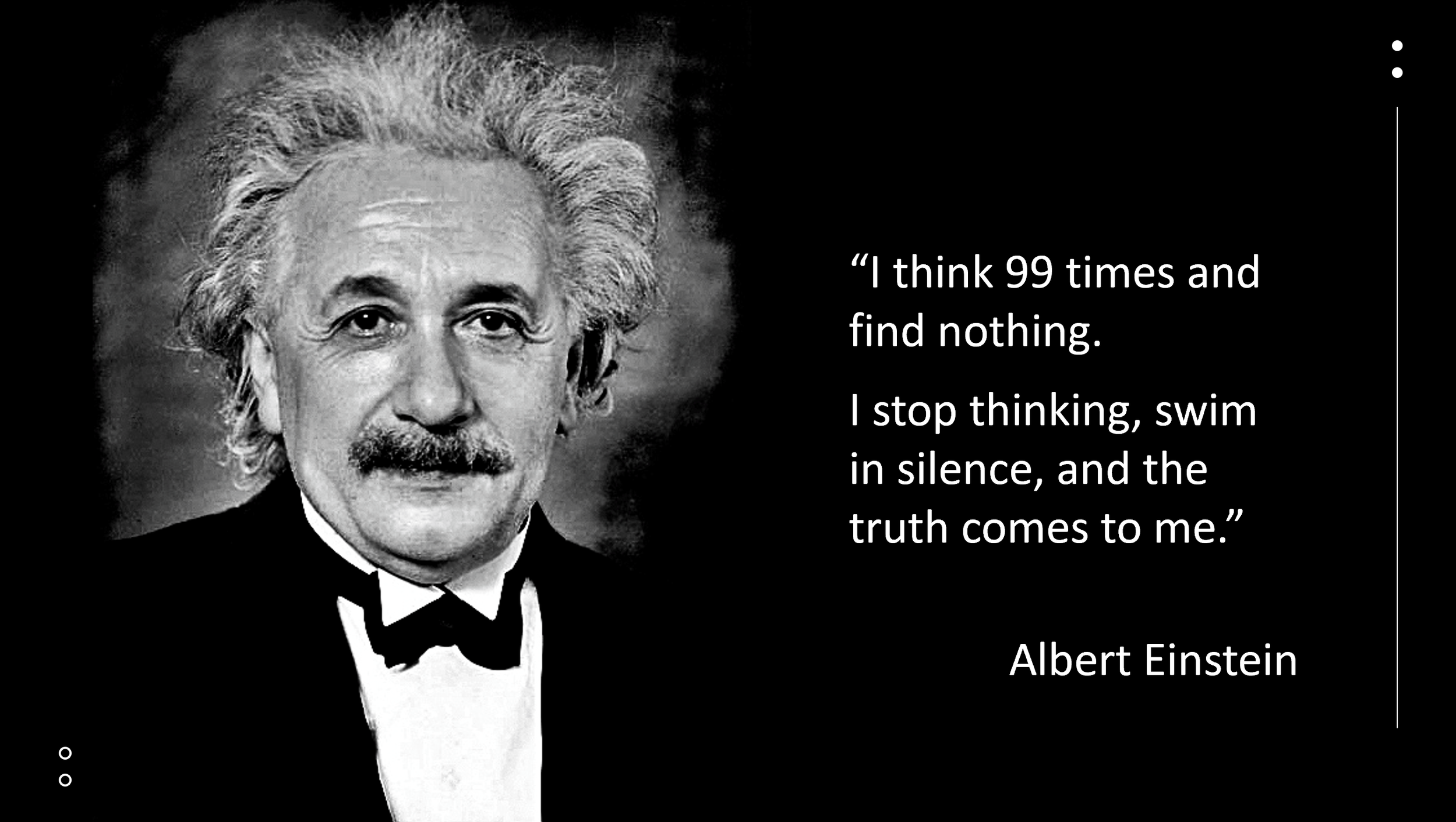

And for just a quick glimpse into the creative value of submerging yourself into one of these liminal states, I love this quote from Einstein:

Photo from Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Hildegard of Bingen, one of my heroes—an incredible 12th-century mystic, writer, and composer—says:

Photo from Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

And this brings me to:

Part II: Creation as a Liminal Process

So you find the courage to go there. You open the vein—the door to the unconscious—so you can receive its transmissions.

Photo by S. K. Kruse

But while you’re there, you’re still conscious, and at least in writing you’re not a complete automaton. Best case scenario, you get into a flow state, but even then—and maybe this is just me because I haven’t yet mastered my craft—I feel myself reaching for words, anticipating how I want to end a chapter.

And if you think about that quote from Einstein, his ideas emerge when he’s swimming in silence, but it’s doubtful—though not completely impossible, I suppose—that while swimming in silence he would have come to his general theory of relativity if he hadn’t been trained in physics. All his knowledge and training came to bear on what emerged in him while he was swimming in silence. So I think any creative work arises from a place that receives inputs from the conscious and the unconscious, and the creator of the work must be proficient in both realms.

If you look at the early works of artists who started new schools—like Picasso—you can see all the work they did in their early years mastering the craft, imitating what they knew before they had their big breakthrough, like Picasso with his Cubist style.

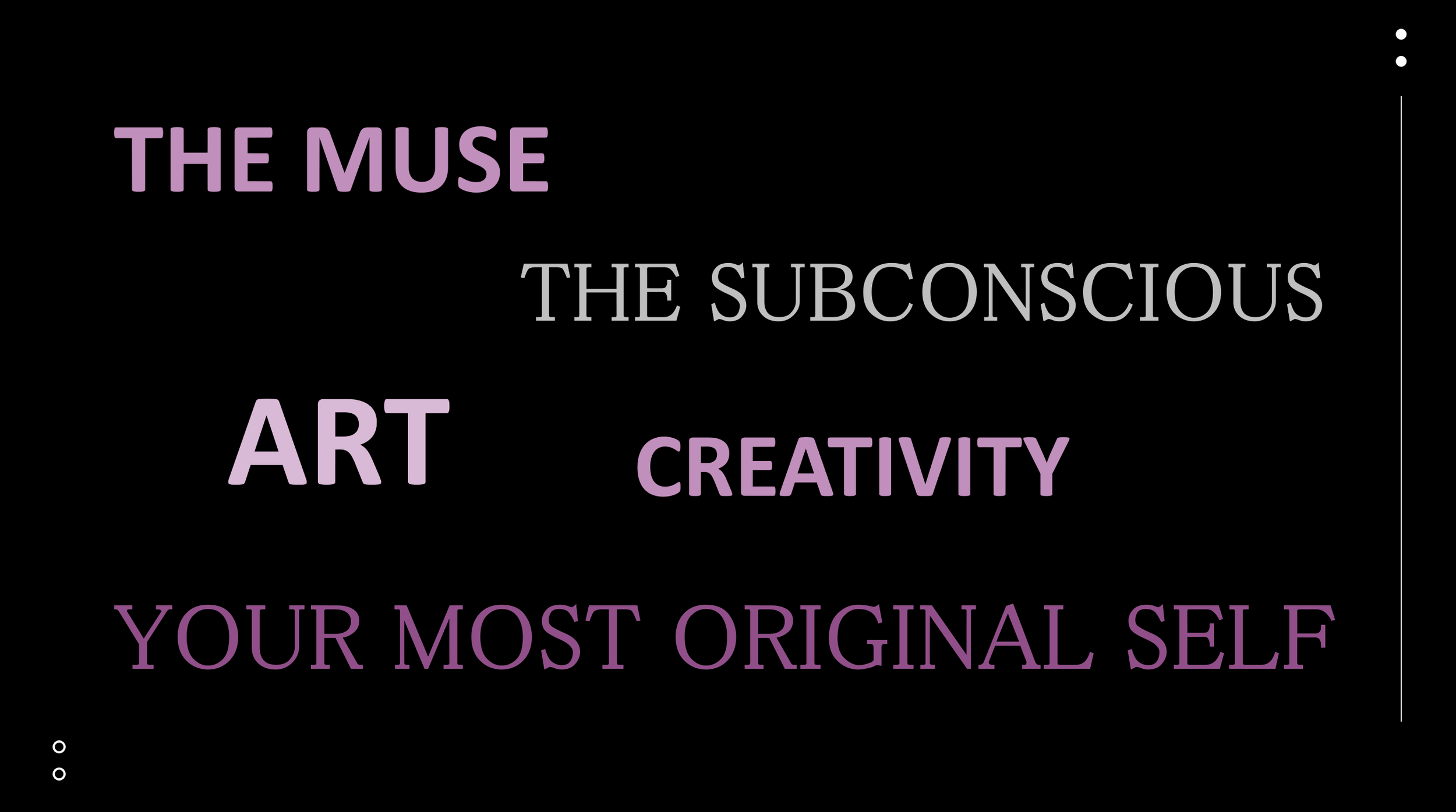

There are a lot of different ways to conceptualize creation as a liminal process—various metaphors and terms to describe these two realms:

I like to conceptualize them using the scheme of the Apollonian and the Dionysian, which I’ve adapted from Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy. And when I say adapted, I mean like he might be rolling over in his grave at how I’m using his terms. He’s not always the clearest about what he means, and the idea contains a lot for him. This is just my little distillation that’s been helpful as I’ve tried to approach writing from a liminal place.

The Apollonian has come to represent for me the form the content takes, mediated by and through the artist’s chosen art form, skill, and knowledge, as well as things like the artist’s experiences, beliefs, temperament, personality, and culture—though these latter elements seem more fluid, penetrating the unconscious as well.

The Dionysian has come to represent for me the unconscious: the source of all gnosis, whose depths the artist can access only through submersion in that liminal interior state.

I keep these two figures of Dionysus and Apollo in my office as a reminder of the necessity of both, because if you write without skill, no one is going to want to read what you write. But if you write without accessing the depths, you’re just creating content.

Photos by S. K. Kruse

Even if you’re in the ultimate flow state when you’re writing and it seems like you’re almost taking dictation, when you read what you’ve written afterwards you still recognize words you’ve loved since sixth grade, the quirky juxtaposition of elements that are a trademark of your writing, the questions that have plagued you since childhood. And all that time you spent learning how to describe emotion and create character arcs, and all the novels you’ve read and short stories you’ve analyzed, all the work you’ve done to try to become a master of your craft was at your disposal—which suggests to me that creation happens in the borderlands of your psyche, where you have access to both realms.

Photo by S. K. Kruse

Part III: Art as Liminal Phenomenon

So if the creator is a liminal being and creation is a liminal process, art then is a liminal phenomenon. So maybe it’s time to define what I mean by Art. Now, I’m no scholar of aesthetics, but I worked up my own little definition of art as skillful and authentic creative expression with a gnostic character. In this definition, “skillful” refers to the proficient execution of the essential components of the art form, while “gnostic” refers to the numinous element of art arising from the unconscious.

And while this numinosity—another term Rudolph Otto gave us in The Idea of the Holy—often has a character of gravitas and pathos like we encounter in the Greek tragedies, it can also be sublime and rapturous, like we get in Beethoven’s Ode to Joy. It can communicate the humbler but no less stirring beauty and goodness of friendship, like in Rowling’s Harry Potter series, or the heart-wrenching fusion of suffering and hope we hear in the spirituals of enslaved African Americans.

“Authentic” refers to the individuated character of the artwork, original and true to its creator, arising from the gnosis of the unconscious and mediated through the artist’s chosen art form, skill, knowledge, experiences, beliefs, temperament, personality, and culture.

I think when these three elements (skillful, gnostic, and authentic) are present and in their fullest expression, we get such masterworks as the novels of Morrison and Hugo, the paintings of Dali and Bosch, the compositions of Mozart and Wellington, the poems of Dickinson and Hughes, the albums of Pink Floyd and Kendrick Lamar—works of sui generis that evoke powerful responses in us.

Photos from Wikimedia Commons CCL: The Paintings of Dali and Bosch

And if we’re looking for a methodology or an order of operations for creating art, I personally think it’s worth paying attention to anything Antoni Gaudi has to say on the matter, as there are few creators in the history of humanity who have brought forth such original and magnificent works as the Sagrada Familia.

Ceiling of the Sagrada Familia by S. K. Kruse

Gaudi says:

Photo from Wikipedia Public Domain

Maya Angelou tells us:

Photo via Wikipedia by Henry Monroe from the 1969 first-edition dust jacket of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

My own experience tells me this is true.

I spent about a decade writing two novels that I cared deeply about, but they weren’t going anywhere. I couldn’t get a publisher. I couldn’t get an agent. And part of the problem, I’m sure, was that I was still developing my skills as a writer, but the other problem was the subject matter I’m interested in—which is all this sort of thing. So I decided a few years ago to write a novel that was “commercial” so I could break into publishing. Now I spent a whole year doing this, and the whole time I was sort of bracing myself as I wrote it, and when I was through, I absolutely hated it. I was disgusted by it. My heart was never in it, and there was no way I was going to put it out into the world.

Then I was even more demoralized.

And then Covid hit, and our family decided to try to make the most of that liminal time. And as I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do with the time, I thought, well, I could write—but I’d used up all my big ideas, including on this novel that I hated.

Then it occurred to me that I could go back to my first love, which was short stories.

As I mentioned, I resolved that I would never again write something that didn’t arise from my Authentic Original Self—to use Bradbury’s term—and I sat down and wrote the bulk of the stories in my collection, Tales from the Liminal, in that interior contemplative state. And then I got a publisher for that.

And then because I got that published, it helped me to get an agent for one of the books I’d written that I loved.

So now I’m going back to that waste of a novel I spent a year writing because I actually really like the characters and the setting. It’s just my heart wasn’t in the story I was telling, so I’m going to try to rewrite it from that interior liminal space, letting it arise from within me—writing something that I love.

And this brings me to my final point. I’d like to conclude with some brief remarks on:

Part IV: Life as Art

As I mentioned, I’m no scholar of aesthetics, and I’m certainly no scholar of Nietzsche, but you can’t help engage with him when you’re thinking about these things because he has so many big ideas on the topic. In The Birth of Tragedy, he also posits:

Photo from Wikipedia Public Domain

This is his answer to the pessimism of Schopenhauer and to the wisdom of Silenus who, when forced by King Midas to reveal to him the truth of existence, says:

Photo from Wikipedia Public Domain

So bleak.

And while I’m not sure I agree that existence can only be justified as an aesthetic phenomenon, I do think by my little definition of art, life is fullest when it aspires to skillful and authentic creative expression with a gnostic character…

which means, of course, we must be capable and willing to visit—to dwell—in the borderlands within.

And if we find the courage to live this way…

Thank you.

If you’d like to find out more about Tales From the Liminal, visit skkruse.com. Print and audio editions are available at your favorite bookstore and on your favorite online platform.

Thanks again for listening, and as the Ferryman says to his brother Death in one of these tales:

Subscribe to

Libations From the Liminal

If you’d like to receive my semi-monthly newsletter

Libations From the Liminal in your inbox, you can sign up here.

You’ll get stories, poems, essays, updates, links, and more!

Newsletter is published through Substack.

You don’t have to download the app.

There is no newsletter subscription fee.

Or if you’re old school, here’s the RSS feed!